It’s probably fair to say that many of us have a starry-eyed view of what it must be like to work in the entertainment industry.

All those red carpet moments, confected though they are, glamorous two-minute pieces on entertainment reporting shows and the general aura of rose-tinted dreams being realised, all but convince that here is life as it should be lived – exciting, fulfilling, amazing, extraordinary.

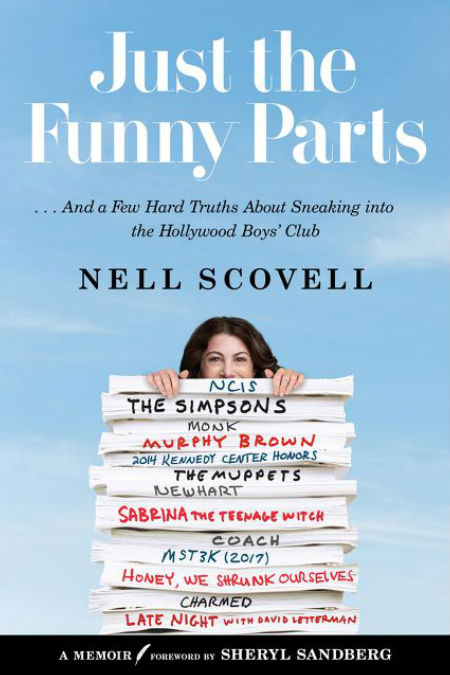

But as Nell Scovell, who was worked on some pretty impressive shows and events in her 30-plus years in showbiz, confesses, while there are some genuinely awestruck moments when life seems almost magical, just as advertised, there are a good many more, the majority in fact, that are downright disappointing and demoralising.

Especially if you’re a woman in an industry dominated by men who seem to think, with some notable exceptions, that a woman’s point of view is either unnecessary or a cumbersome hindrance, a distraction from the fine business of making Peak TV and cinematic wonders.

But, of course, that’s ridiculous, since as Scovell points again and again, women brings wholly different, enriching perspectives to all kinds of stories, and by denying them adequate representation, or any representation at all, you’re failing them and society as a whole who are robbed of the unique insight female writers bring to the showbiz table.

“If real estate’s mantra is ‘location, location, location”, show biz mantra’s is ‘talent, talent, talent’. No, wait. That’s what it should be. Instead it’s ‘connections, connections, connections’.” (P. 37)

It seems obvious to you and me how much better everything is when diverse viewpoints are included; it doesn’t matter if its woman, LGBTQI+, people of colour and everyone else in our gloriously multi-hued world – give people a voice and any story suddenly comes alive with all kinds of amazing new perspectives.

Alas, what is obvious seems to fly well under the radar in good old Hollywood.

Take Scovell’s stint as a writer on Late Night, at that point hosted by Dave Letterman, where she encountered an atmosphere best described as “Harvard Lampoon frat house” where being a woman (Scovell was only the second hired ever after Merrill Markoe) or a person of colour (none hired between 1982 and 2015) was so criminally rare.

With a mix of biting commentary and good humour, a hall mark of the book as a whole and Scovell’s TV writing in particular – she also worked as a journalist for a number of years at Vanity Fair and SPY which near-universally happy times in her impressive career – Scovell details how hard it was to make inroads when everything was structurally arrayed against you.

Time and again Scovell encounters a glass ceiling so thick and impenetrable that it might as well have been solid brick, obstacles that she often overcame through tenacity or by playing the game as best she could, but all which spoke to an industry where the boys’ club was well-entrenched and decisions were made behind her back (see her stint on the revived The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour).

Scovell, who proves herself an astute and funny observer of her years in the industry, balances the dark times, and there was unfortunately far too many, with the good times, the great friendships, the enriching career experiences and wonderful opportunities that came her way.

Her time on Coach for instance, was a highlight, buoyed by the superlative mentoring of her boss Barry Kemp; so too her time as a showrunner on the first season of Sabrina the Teenage Witch – this ultimately proved something she had to leave but for reasons not necessarily related to gender inequity – and as a Supervising Producer on Murphy Brown where the “three Ps” (people, product and the process) uniquely and pleasurably aligned.

What is startling is not that these types of experiences existed – Scovell is happy to admit when they did and how good they were, her enthusiasm and gratitude a joy to witness – but how little time many of them lasted.

Her stint at Newhart, where she had a lovely, four-word encounter with the star himself, lasted a scant nine months, and the revival of The Muppets just a year; as Scovell makes clear, without a hint of defensiveness or bitterness, this is simply how the dynamics of showbiz, where talent and accomplishment are often sidelined by politics and posturing, often play out. (This mayfly-like lifespan of a TV writer forms the narrative structure of this highly-entertaining and eye-opening memoir which details her rise, plateau and fall/rise, a rollercoaster of ups and downs that is common for almost all writers.)

“At the exact age of twenty-nine, I opened The New York Times Book review and thought ‘How nice! Kurt Vonnegut, one of my favourite novelists, wrote an essay.’ One paragraph later, I felt sucker-punched. here’s what Vonnegut wrote:

‘If Lloyds of London offered policies promising to compensate comical writers for losses of sense of humor [sic], its actuaries could count in such a loss occurring on average at 63 for men, and for women at 29, say.’

Say what?

My comedy career was justt aking off and now someone I respected was predicting that I’d lose my sense of humour—the source of my livelihood—at any moment. And why did men get thirty-four more years of being funny than me?” (PP. 203-204)

But though Scovell is professionally sanguine about the good and the bad, she is hardly an unfeeling robot.

In often emotionally-charged, laid bare chapters, she is upfront about the toll the many disappointments in her career have taken on her, and while she admits these short-lived stints befall male writers too, it is a particular issue for women who are still fighting, even in the transformative #MeToo movement era, for an equal seat at the entertainment table.

For all her seamlessly and warmly-delivered anecdotes, and her willingness to joke and wryly observe to engaging effect, Scovell is frank about the way women are often sidelined, diminished and restricted to quotas in writing rooms which continue to be male-dominated for the most part.

The inspiring thing is that for all her setbacks and disappointments, and they have been legion along with all the fulfilling times where “passion and contribution”, as her friend and sometime-collaborator Sheryl Sandberg, Chief Operating Officer of Facebook, terms it, came together, Scovell remains in love with her craft and eager to keep going on and on as she declares in what is perhaps one of the most perfect endings to any memoir I’ve read:

“Thirty years after I broke into Hollywood, I’m still pressing that lever hoping for a pellet. In an ideal world, I’d get to direct another movie. Or maybe I’ll create and run another show. I just want one more shot.

And then one more shot after that.

And then …”