We are captives of our calendars.

How else to explain the way looming dates, particularly those for major life events, send us into a flurry of activity and anxiety, a maelstrom of hoping and wishing, planning and organising that in the end, Shakespeare be paraphrased, amount to nothing? Or at least, not what we expected them to?

Arthur Less is a man painfully aware of the machinations of its time and its cruel, unrelenting march to places hoped for but not quite realised; or as he sees it, dreamt of in the heady days of optimistic youth.

A mid-tier writer, as he seems himself, he lives in San Francisco in a home gifted to him by his much older, ex-lover Robert, a man who loved him fiercely but who received nowhere near the same amount of love in return.

This relationship is, in many ways, emblematic of Arthur’s life; an easy cavalcade of moments, one tumbling into the other, neither particular bad not especially remarkable, the dynamic of a person who has had life fall easily and cosily into his lap to such an extent that he hasn’t had to strive or self-examine how it’s all coming together.

It hasn’t troubled Arthur until now, but as he approaches his 50th birthday, and the wedding of Freddy Pelu, the man who got away, to someone definitely not him, Arthur finally faces an existential reckoning, one which causes him to accept an eclectic array of events from around the world simply to get away/

“The Garden of Bad Gays. Who knew there was such a thing? Here, all this time, Less thought he was merely a bad writer. A bad lover, a bad friend, a bad son. Apparently the condition is worse; he is bad at being himself. At least, he thinks, looking across the room to where Finely is amusing the hostess, I’m not short.” (P. 145)

It is not, as you might expect, an attempt to elude the weighty banalities of everyday life, an idyll of time free from the flipping of calendar pages in which he can reason through where his life has got to, and why.

That is how it turns out, in effect, but when Arthur leaves his home for events as diverse as teaching at a German university and reviewing restaurants in Japan, and mismatched program of all kinds of quirky oddities in-between, he simply wants to forgot about letting Freddy go.

Dear lovely, caring Freddy, the adopted son of his frenemy Carlos – he stepped into adopt his nephew Freddy when the young boy’s parents died – who acted as casual as Arthur demanded but who, almost too late, realises he loved the author far more than as a sexual plaything.

Arthur, of course, didn’t help, so used to things simply happening to him, with little to no active effort, that he ended not value things and people as highly as he should.

When he finally does start coming around to evaluating the dips, rises and contours of easily-begotten life, somewhere between Germany and Japan, and other points in-between, he comes to appreciate that this negligently chilled attitude of his has cost him a great deal.

Of course, like all of us, he is far harder on himself than he should be, sinking into despondency and vicious recrimination when the simple acknowledgement of benign wrongs committed and understanding of necessary restitution is all that’s needed.

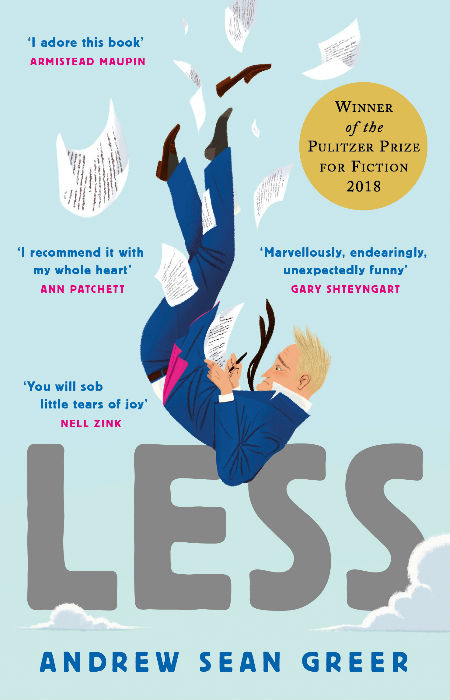

Greer writes Arthur, as he does the entire Pulitzer-prize winning masterpiece that is Less with a lyrical poeticism that is as insightful as it is beautiful.

He avoids that messy, emotionally arms-length place that some writers of exquisitely-lovely prose fall into where the words are a thing of breathtaking beauty but the humanity is lost somewhere in the lustrous prose.

Less never once falls into sounding wonderful but meaning little, or feeling like it means little, netherworld where characters pontificate at length about life and its many vagaries but end up sounding weirdly removed from the harsh realities of life real or imagined.

“But could she also have discovered his other crimes and inadequacies? How he made up ceremonies for a fifth-grade report on the religions of Iceland? How he shoplifted acne cream in high school? How he cheated on Robert so terribly? How he is a “bad gay”? And a bad writer? How he let Freddy Pelu walk out of his life? Shriek, shriek, shriek; it is almost Greek in its fury. A harpy sent down to punish Less at last.” (P. 249).

At every point, no matter how poetically Greer dispense with the narrative or Arthur’s great and small, actual or perceived agonies, does the book ever feel anything less than absolutely real.

Everything about the crisis into which Arthur plunges unexpectedly – he think he’s escaping the wedding of his one great love but in reality he’s walking straight into an accidentally self-appointed review of his entire life and the reasons for living it – feels like it come happen to anyone of us.

Granted, it likely wouldn’t sound anywhere near as poetically-pleasing since though we wish we could speak like characters in a well-written book like Less, we really do; instead we are left floundering in a sea of half-realised epiphanies and poorly-articulated insights, aware we are on the road to Damascus but not entirely sure what we should be doing while we’re on it or when we will know we have arrived.

If we ever arrive, since life is rarely that clean-cut or definitive.

Less is a well-deserved Pulitzer Prize winner, speaking to the human condition – one in this case suffused with a gay sensibility since Arthur and many of the characters either are, or are comfortable inhabiting that world but which never feels less than universal every step of the way – in a way that feels intrinsically, deeply relatable, beyond gorgeous in its articulation but never losing the sense that here is something we should be heeding, whatever it is we might be running from.