Depending on how whose etymology you believe, many a person has observed and subsequently remarked that the first casualty of war is truth.

Truth is twisted or downright ignored during conflict for a variety of reasons – keeping the enemy in the dark, elevating the good spirits of a beleaguered citizenry upon whose support many a war’s successful prosecution depends, or simply ensuring that the good news keep rolling in a time when the bad stuff is well and truly thick on the ground.

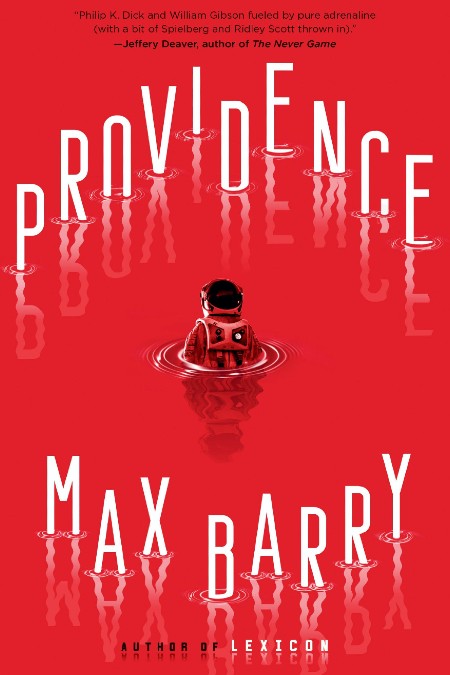

In Max Barry’s superlatively meditative sci-fi thriller, Providence, named after the gigantic AI-controlled battle cruisers that are fighting a hive-based, amphibian-like alien enemy, but also the idea that god or nature knows better than you and is protecting in ways beyond your comprehension, truth has well and truly taken a back seat to the jingoistic need to keep the people of Earth behind the war effort.

After years of battling the “Salamander” hordes, as they have been colloquially named, and the loss of thousands upon thousands of lives and the expenditure of vast sums of money, everyone is tired and exhausted by a war being fought so far away, trillions of miles in fact, that it hardly seems real anymore.

The reality is that while people might be tired of the titanic battle between humanity and alien, it goes on nonetheless, with every battle lost to this enemy bringing them one step closer to annihilation of our fair blue planet and all who dwell upon it.

The thing is, anecdotal evidence aside, there is no firm evidence that the Salamanders are really a hostile force bent on genocide.

“They fell into patterns. Each day, Gilly rose, ate in the mess with whomever he was sharing a duty rotation that day, and performed ship maintenance. Sometimes he wrote reports for Service. He recorded clips. When the klaxon sounded, he attended station. The engagements changed in the details, but the underlying dynamic was always the same, always salamanders dying in the hundreds before they could get anywhere near enough to spit a huk. It became routine, and occasionally he felt his mind drifting, as if he were watching a movie he’d seen before and knew by heart.” (P. 29)

The first contact video that has gone viral on the manically buoyant social media networks of Earth would suggest they are, since it seems to indicate a kill first and to hell with questions later approach by the swarming species.

But no one has actually held a conversation with, intelligence is spotty at best and so the assumption is they mean us harm and we must fight back.

Here truth is a shaky concept, one drawn from anecdotal evidence but not backed up by any certainty (until later in the book when some surprising facts emerge); suffice to say, they attack, we fight back and no one has any time to investigate further.

Based on the evidence alone, war veteran Jackson and captain of Providence ship #5, Life officer Beanfield, Weapons officer Anders and Intel specialist Gilly (the only civilian onboard) are sent off to the far reaches of space to fight the supposedly good fight, selected by AI minds as the perfect crew combination and prepped and readied for a social media charm offensive every step of the way.

While Service, the US-based military group controlling the missions, gets all the useful intelligence unfiltered from all the Providence teams out in deep space, the public is fed a diet of peppy video feeds, empowering speeches and “authentic” reflections on what it is like to be combatant in the greatest war humanity has ever faced.

Truth is surplus to requirements when it comes to publicly-consumptive propaganda and Service knows it, the crews knows it and anyone within the bubble overseeing the war knows it.

However, truth always finds itself sidelined in other insightful, clever ways in Barry’s masterful work.

Each of the crew members, bar possibly Jackson who survived one near massacre to go on another mission despite an abiding sense that she shouldn’t, believes their role in the mission is another thing entirely to what it is and when the truth emerges, it becomes for them to function as a team on a journey that increasingly feels like it has a repetitive, pre-ordained outcome.

Barry artfully examines what happens to the psyche of people who are told one thing is true, find out quite another is in fact the case and who have no choice but to function effectively in the middle of it all.

As the AI picks and chooses their battles, with a decreasing effectiveness that suggests the truth about a seemingly infallible fighting machine may be yet another casualty of a war that goes from feeling remote and far off to a deadly, all-hands battle for survival.

Barry slowly but surely ratchets up the terror, the stress and the psychological strain until what began as a meditative reflection on war, truth and the grey areas inbetween – nothing is ever black and white as the team slowly begins to discover – violently explodes into a terrifying scrabble for survival.

“Flames cackled. His sense of direction was wrong. He was looking into the nose of the jet, which was filling with thick curls of winding black smoke, but it felt like up, not forward. Down was behind and a metric fuckton of gravity was trying to usher him in that direction. They had ditched, then. He hoped he hadn’t killed Beanfield. He looked at her. ‘Beanfield,’ he said. She didn’t respond.” (P. 211)

Providence expertly deliver good old-fashioned, terror-filled action at the same time as it winningly takes us into a future-driven but present-prescient exploration of data versus humanity, truth versus situationally convenient information.

It is the perfect mix of thought and action, a novel that keeps you turning the pages at a fiendishly fast speed while stopping to think, sometimes a few times a page, about how often we accept something is truth when the polar opposite is true, or more usually, sits in the grey messy areas between absolute certainties.

Are the aliens really evil? Is humanity really good? Or are we both a mix of the two? Should truth always be allowed to prevail because that is the idealistic thing to do or does exposing what is really going on risk far more important things down the line?

There’s so much to think about in Providence, even as you hold tight to each twist and turn of the thoughtful, ever-accelerating narrative, a brilliantly-clever book that thrusts you headlong into a war and the effects it has on the populace of Earth in general and four people in particular, while asking with intelligence and insight if the war should be happening at all, and if so, what we are willing to sacrifice, including truth, to see it through to a hopefully successful conclusion.

And just as, if not importantly, what will be left in its wake, and if we are able to live with the consequences which will likely not be anything like we have been led to believe.