One of the cruellest fates that can befall a person is that of becoming “marooned in time”.

That is, to watch helplessly as, one by one, your contemporaries die around you, taking with them all your commonly shared memories, cultural touchstones, and common experiences, leaving you alone to remember what was once was and can never be again.

It is a cruel punishment, a separation of sorts from the usual chronological ebb and flow of the world around you, but fortunately one only visited on people towards the end of what are hopefully long and fruitful lives.

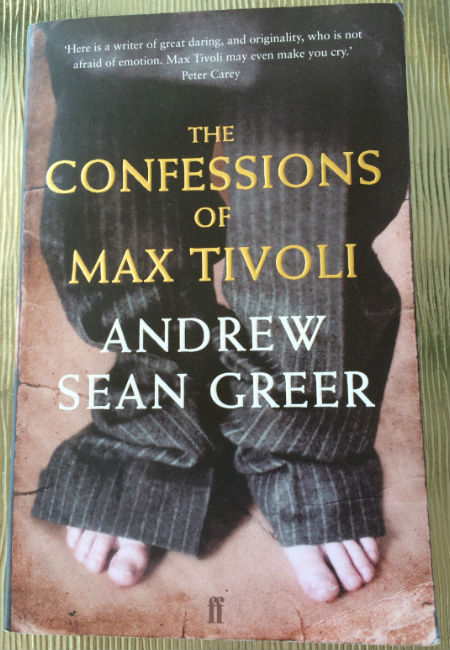

“So many things stand in the way of anyone ever hearing my story. There is a dead body to explain. A woman three times loved. A friend betrayed. And a boy long sought for. So I will get to the end first and tell you we are each the love of someone’s life.” (p 3)

For Max Tivoli though, cursed by a rare medical condition to look like an old man when he is but a child, and a child in the twilight of his years, being marooned in time is a lifelong cruel reality of being, one always out of sync with the people around him, from whom he is always forced to conceal the nature of his true self.

And with whom he is always forced to relate from a distance even when he is agonisingly close to them, and in the case of the love of his life, Alice, passionately, deeply, impossibly in love with them.

His only recourse is putting the mostly hidden events of his life – he is only able to be truly himself with his close friend Hugh Dempsey, and to a far lesser extent his mother and sister Mina – down on paper; hence The Confessions of Max Tivoli, as “chronicled” by gifted writer Andrew Sean Greer.

This book of exquisitely rendered prose, which captures every last nuance of Max’s joys, longings and emotional frustrations with the sort of poetic yet beautiful melancholy that makes your heart burst over and over, is testament to one man’s reluctance to let the bizarre circumstances of his life defeat him.

He is denied much that is true, forced always to be something he is not on the outside and unable to truly express who he is on the inside, and there are times where you wonder how it is he manages to keep one foot in front of the other but for all the things he has lost, there are things that he gains, even if from afar and only in part, and it is these small gifts, most particularly the love of his beloved Alice which takes on three distinct forms throughout his life, that sustain him through an otherwise blighted existence.

What is most remarkable about The Confessions of Max Tivoli is that it is largely buoyed by hope and desire, and unforeseen moments of humour, when all the expectations should be that it would fatally weighed down by the melancholic pressure of Max’s unusual condition.

“As the years passed, my only companions were my sister, my mother, and Hughie. I was the priest of Alice, keeping the sacred embers glowing until her return, and then, when I could learn nothing of her whereabouts and as the years passed on without her, I became the widow to my own hopes.” (p 92)

That Max’s tale manages to rise about this “slough of despond”, as John Bunyan evocatively terms it in Pilgrim’s Progress, owes much to Greer’s willingness to be unflinchingly honest about Max’s state of heart and mind, a perspective that grants us insight into both the highs and lows of this most physically unusual of men, but most pertinently to the fact that he is as much in love with life and those who fill it as anyone else would be.

He is after all, a quite ordinary man in that sense, as burdened by life’s gifts and curses, its capacity to give greatly and withhold much, as anyone else, and it is this innate relatable humanity that Greer brings most beautifully and heart-rendingly to page after page.

And yet Max is so much more than ordinary in one crucial sense – he has to fight for every last inch of happiness in his life far more than any of the people around him who take life’s ups and downs with an almost casual air of resignation or acceptance.

Whether this manifests itself as an almost endless road trip across USA with his best friend Hughie (who reveals in one part of the book that he has just as much to hide as Max does rendering him in Max’s parlance, a fellow “monster”) to find his long-lost Alice, or assuming an identity that is not his own and effectively killing himself off in order to win his much-treasured prize of true love, it is an all or nothing proposition, a passionate affair with love itself that does not diminish over time, even though there is much that comes against it, not the least the unforgiving passage of life itself.

“It’s one thing to disguise oneself for an afternoon tea or carriage ride; it’s quite another to keep a lie for the length of an affair or, more improbably, for the lifetime that I hoped to be with Alice. I might change my looks and words to suit her, but how could she really love me when my truest self was buried under the floorboards?” (p 138)

Max is accused at times, most affectingly by Hughie towards the end of their lives when the former’s decision to give everything up to have Alice close to him has devastating effects on the latter’s life, of being selfish; but then he is almost forced to be more selfish than the rest of us since he lost so much before he had barely left the womb.

The real genius of The Confessions of Max Tivoli is that its protagonist does not ultimately emerge as the monster he often accuses himself of being but rather an ordinary man in search of love, life and happiness, who is forced by a most extraordinary set of circumstances to do everything he can to gain the very things the rest of us take for granted.