It is one thing to love a book; quite another to fall so headlong in love with it that reading it feels like you’ve come home.

In the latter scenario, it’s as if this was the book you were always meant to read, one that will stay in your heart and be recalled with fondness long after other books read in the same period, while valued, have faded into hazy recollection.

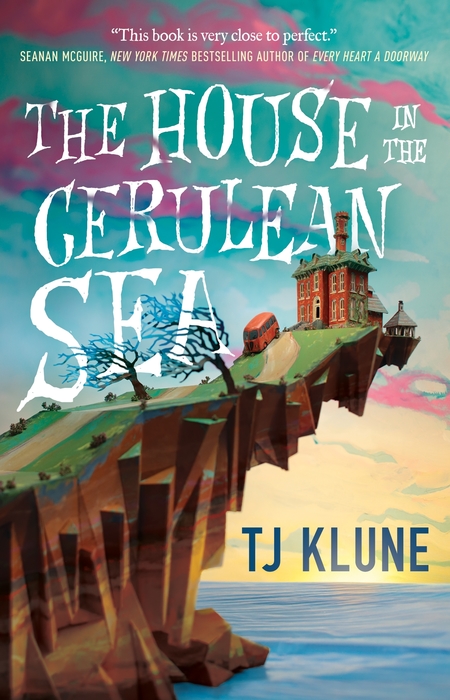

The House in the Cerulean Sea by T. J. Klune is just such a book, a novel so perfectly wrought that it is hard to find fault with it in any way, shape or form.

Much of its appeal lies with the fact that the author appears to have poured his entire heart and soul into almost 400 pages of rich, funny and poignant writing that gets right to the heart of how wondrous it feels to finally find a place you can call home.

A queer heart-on-his-sleeve writer, Klune clearly understands how important it is for other queer people, such as this reviewer, to see themselves and their stories reflected in the books they read and he has invested every last gram of that understanding is a book that quite often feels like a reassuring hug, a confirmation that just because you are different doesn’t mean there is something wrong with you.

When that’s the message you have heard all your life, it can feel like someone throwing you a life buoy when you come across a novel like The House in the Cerulean Sea which lives and breathes with passionate vivacity the idea that you are special and unique no matter how different to mainstream ideas of normal you might be.

“She was amused. ‘Linus. I head you had quite the adventure.’

‘Indeed. A bit out of my comfort zone.’

‘I expect that’s how most explorers feel when they step out of the only world they know for the first time.’

‘You often say one thing while meaning another, don’t you?’

She grinned. ‘I have no idea what you’re talking about.'” (P. 189)

Now, you might think at this point, that that message sounds like the sort of trite bumper sticker philosophy that people bandy about on social media to seem like happily woke and in touch with the social avant garde but it’s absolutely nothing of the kind.

In fact, what Klune has created in this gorgeously delightful book which resonates with authentically heart messages of belonging and inclusion is nothing short of a real world declaration of what it means to be truly, wonderfully and deeply human.

Which is interesting because many of the characters at the heart of The House in the Cerulean Sea, and what a big and all encompassing heart it is, are as far from human as you can get, or to be more accurate, as far from mainstream ideas of human as you can get.

The protagonist Linus Baker is as cookie cutter and straitlaced by-the-books as you can get as a person, a case worker in the Department in Charge of Magical Youth (DICOMY), who spends his lacklustre and uneventful days checking on the state of magically-imbued children who in the department’s misnamed “orphanages”.

But beyond him sits an array of characters an mysterious island at the end of the line whom Linus is sent to check out an hush-hush mission by Extremely Upper Management, all tagged by DICOMY as dangerous and problematic, from house master Arthur Parnassus and his house mistress Zoe, to six quite extraordinary children who turn out to be far more wonderful and complex than their threadbare case files might suggest.

At first, Linus, who bears his own secret and is as repressed as it possible for a person to get, is determined to be as objective as possible.

It all part of the RULES AND REGULATIONS, a fossilised decades-old guide to how to do his job, that Linus lives by near religiously, the book an outgrowth of an unfeeling, cruelly separatist mindset that has spawned societal campaigns such as “SEE SOMETHING, SAY SOMETHING”, an initially well-intentioned program to keep those who don’t fit the mainstream mold safe which has morphed over time into a draconian instrument of otherness, bigotry and discrimination.

Linus is far from being a cold enforcer of the established order; he is at heart a good and decent man who actually gives a damn about looking after the kids in the orphanages he investigates but he has slowly walled over who he is as a person, both fearful of what his true queer nature might do to his carefully-ordered existence and constrained by a system that look to powerfully all-consuming to ever be fought.

But as he comes to know Arthur and grows to like him far more than is objectively proper, and falls in love each of the six kids in Arthur’s care, all of whom are so richly, imaginatively and empathetically drawn that you can’t help but fall in love with them too, all his old ideas about what is important and who he is go flying out the window in a revelation as powerful as his first glimpse of the cerulean sea that surrounds the island on which Arthur’s sanctuary sits.

“‘It’s not my home,’ Linus admitted quietly. ‘I live in the city.’

Helen scoffed. ‘A hoke isn’t always the house we live in. It’s also the people we choose to surround ourselves with. You may not live on the island, but you can’t tell me it’s not your home. Your bubble, Mr. Baker. It’s been popped. Why would you allow it to grow around you again?'” (P. 281)

Watching Linus transform is an unmitigated, deliciously heart-filled joy, the emotional backbone of a novel that nails its colours to the mast firmly and without apology but does so in a way that is less polemic, though there is definitely a pleasing flavour of that throughout, than giddily, soul-inspiringly human.

During the month that Linus spends on the island, that sits across from a village where suspicion and hatred of Others is rife, he comes to understand that his home and his family is not back in the perpetually rainswept capital where he lives a small “l” life in a small house from where he goes to suffocatingly circumscribed house, but here with the people whom far too much of society condemns as unconscionably different.

The House in the Cerulean Sea is a vivacious joy because it not only celebrates how glorious it is to be different but also makes it reassuringly clear how often even in that difference there is a commonality of human experience that the small-minded and the bigoted miss on their cursory assessments of those who don’t fit their idea of normal.

In its own quirkily upbeat and happily determined and tender way, The House in the Cerulean Sea gloriously celebrates how good it feels to find your special place in this world, one which can diabolically cruel and nasty but can also offer the type of unconditional love and acceptance that so many people of all shapes, sizes and types crave and deserve.

That Linus finds this is a beautiful, heartstoppingly wondrous thing but that we are taken on this life reshaping journey with him is a real treat and privilege, something that anyone who has ever felt outcast will love, adore and cling to, proof that we are never alone once we find our family with the book also a reminder that once we find them, we must hold tight to them, fight for them and treasure them for the rest of our natural, or unnatural, life, whatever the case may be.