Life does not usually afford us too many do-overs.

Captive to a headlong rush down the chronological racetrack, you’re lucky if you have the chance to get it right the first time, let alone again and again until, maybe, possibly, you get it right.

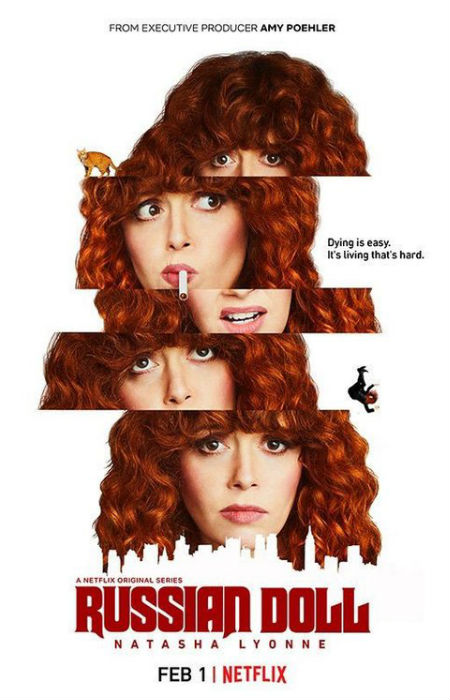

Netflix’s latest smash hit, Russian Doll, not only offers a look at what life might be like if a do-over was a possibility but importantly asks the salient question – would you really want it if was on offer?

Nadia Vulvokov (the brilliantly-quirky Natasha Lyonne), a 36-year-old “cockroach” of a woman – she is called that by her close friend Maxine (Greta Lee) at one point in reference to her seemingly unquenchable intake of drugs, alcohol and sundry other substances, none of which seem to have any lasting effect on her – who finds herself reliving her riotous, drug-fuelled birthday over and over and over again.

To do that, of course, she has to die over and over again, which is, as you might expect is a pretty-unsettling experience.

Unlike 1993’s Groundhog Day, starring the superlative Bill Murray, Nadia doesn’t undergo any great epiphany as a result of her live-die-live-die-live-etc time loop; there is a resolution of sorts, and a reasonably life-affirming one at that, but essentially Nadia’s endless do-over, which sees her vaulting between gung-ho, helpless, euphorically-resigned and pretty much everything in-between, is more of a coming to terms with the shitty life that brought her to this point (and endlessly trying to find her beloved cat, Oatmeal, who is one of the undisputed stars of the show).

A point that doesn’t seem to want to end.

Nadia gives solving it her all, variously nominating the drugs she’s taking, her drug dealer, her friends, sins from her past, her relationship with her flaky, troubled mother, and possibly a homeless man with whom she forms a reasonably-close bond (well, for 24 hours until she dies again) but finding out why she’s trapped in this 24-hour purgatory proves beyond her.

That is, until she meets Alan Silveri (Charlie Barnett) in a lift one day, a lift which crashes to the ground killing them both until they both instantly awake in their respective bathrooms (technically it’s Maxine’s bathroom but honestly Nadia is there so often she should just take possession) to begin their dance with truncated mortality all over again.

While this nightmarish cycle is mined for laughs, dark, twisted, quirky laughs but laughs all the time with Nadia’s various modes of death many and hilariously-varied – she is hit by a taxi, falls down stairs (leading to some very funny conversations with friends who can’t understand why she insists on taking the fire escape) freezes to death, is blown up in a gas explosion and goes into anaphylactic shock after a swarm of bees sting her – at its heart, Russian Doll is, as you might expect of a premise that seems to allow no escape from the same time period, a fairly serious affair.

While Nadia, a computer programmer working in gaming, is a fairly free spirit, not prone to self-examination, largely because that way too much pain lies – her only significant familial relationship is with Ruth (Elizabeth Ashley), a psychotherapist who is the only real maternal figure Nadia has ever known and even she can’t make her wild child “daughter” admit she is running from the spectres of her childhood – her time loop experience eventually forces her to examine a host of things in her life.

Even so, there are no great road to Damascus moments, save for the end (even then, it’s presented less as some cheesy epiphany and more as a natural result of finally confronting your deepest fears and pain), and for the most part, Nadia grapples with the existential ramifications of her (almost) unique predicament in small increments.

For instance, as the limited eight-episode series kicks off, she is unwilling to have anything meaningful to do with her ex, a married-now-divorcing man named John (Yul Vazquez) who is in love with her and clearly wants to revive their relationship which ended six months previously.

As Nadia struggles to come to terms with not only dying over and over but what it means for the limited sliver of life she has at her disposal, she evaluates in ways big and small, and not always successfully, what he means to her and whether there is anything further she wants to pursue with him.

Again, there is no great earth-shattering resolution to this revisiting of romantic wounds past, just as most things, in common with life generally, refuse to tie themselves up neatly and easily in a pretty red bow – which by the way Nadia would hate although you suspect by the end she would be far more tolerant of it occurring – but it is fascinating how her death/life/death etc loop forces a woman infamous for her unwillingness to feel anything or get close to anyone to examine all kinds of things she once considered beyond reach.

In that respect Russian Doll, which is essentially a dark, twisted, quirky comedy, anchored by a brilliantly funny, empathetic and vibrantly alive and vulnerable performance by Lyonne who hits all the right notes and then some – being brusquely, humourously abrasive, with an armada of prickly oneliners at your beck-and-call and stripped to the bone emotionally at all once takes some doing but Lyonne absolutely nails it -is one big giant therapy session.

A fantastically funny, in-your-face therapy session that is full to the brim with moments both confronting and laugh-out-loud, mirroring the weird contrariness of life, and yeah, death, and one that proves addictively viewable, Russian Doll is a show so whip smart funny and cleverly-insightful that you don’t realise how cut-to-the-marrow Nadia is until the laughs are followed by scenes so emotionally haunting you almost gasp as you take them in.

Co-produced by the talented Amy Poehler, Russian Doll doesn’t attempt to solve the mysteries of life or death or to add to the idea that “42” is the meaning of life, and while there will likely be those who want to read a lot more into it, this brazenly fun and clever show seems content to eschew great existential lightbulb moments in favour of brilliantly-lucid moments of humanity which at its best is funny, silly, sad, enlightening and confusing, and an ending which may not make immediate sense but which is heartwarming and uplifting in ways you don’t necessarily need to explain.

3 thoughts on “Dying is easy – it’s living that’s hard: Thoughts on Russian Doll (season 1)”

Comments are closed.