I have always found books to be the most perfect of escapes.

When I was a kid and into my teenage years, they helped me to screen out the bullies, who were damn near omnipresent in life and escape to all kinds of magical, wonderful places, and as an adult they have helped me deal with a world that is often less than pleasant.

Such as when the COVID pandemic starts raging all over again, and you spend four months in lockdown, surrounded in neighbouring suburbs by thousands of cases, and your only way out is by stories, whether on streamed programs, movies or, of course, books.

While I love watching TV (my catch-all term for streaming and television) and movies, it is books to which I almost go when life gets way too hard to deal with, and as lockdown took its whole and I grappled with rising levels of anxiety and depression, it was reading that helped me to feel less ragged, less trapped and far more able to deal with what is not a natural situation.

As usual, my choice in titles ran the eclectic gamut, from science fiction and fantasy to romantic comedies to some searing real life stories but one clear trend that did emerge was that I simply couldn’t handle anything too dark and confronting.

I had a ton of new and TBR titles lined up to read but some of them got discarded because, beautifully written and evocative though they are, they were just that bit too dark and real for a guy struggling to deal with how dark and real life had become.

So, I did the sensible self care thing and put them aside, either permanently – I have two reading friends who have similar tastes and are happy to take books I don’t want (or have read and don’t want to keep) – or for now, happy to escape into books that made my happy or gave me a sense of a life unlimited.

To sum it up, Reality 0 Books 1, which is, when I think about it, pretty much how every year ends up.

Sad Janet by Lucie Britsch

The thing is that in unskilled hands, Janet could simply have been a whining, malcontented pain in the neck, someone staring down what they don’t like, and telling you at volume, why they don’t like it, but with no real new way forward if you decide you have had enough of blindingly and unquestioningly toeing the line.

But with Britsch at the helm, Janet is incredibly likeable and real, a woman who is authentic as they come, an everywoman who doesn’t want to be an everywoman, but who puts into words what the rest of us wannabe free souls desperately wish we could articulate.

The fact too that you know deep down Janet wants to be sort of, kind of, maybe happy, but very much on her own, unmedicated terms, gives her character and Sad Janet as an engaging novel that you will like more and more as you get into it, the kind of offbeat appeal that makes her the kind of protagonist with whom you identify and want to spend time with because she’s so delightfully, openly, goddamn perfectly authentic.

She is that go your own way breathe of fresh air, complete with uncertainties, profanity and unexpected vulnerability, that you never knew you wanted to breathe in, and she makes Sad Janet, which pulses with a heady mix of emotional resonance and barbed, pithy good humour, one of those novels that says a lot and says with a sense of fun and truthfulness such that you will find yourself heartily glad, maybe even happy, you ventured into its life-changingly honest space.

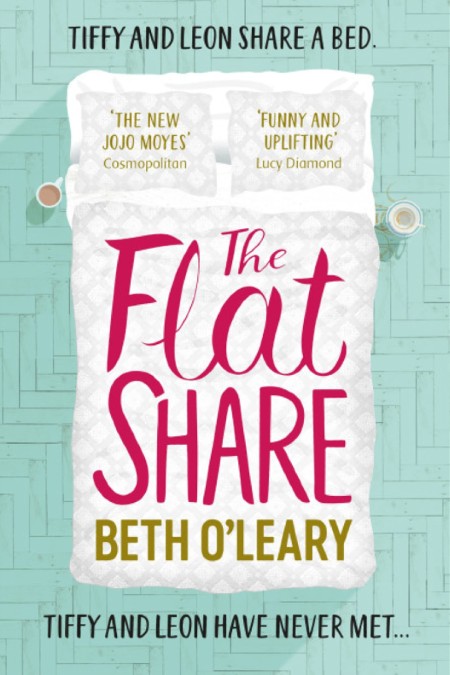

The Flatshare by Beth O’Leary

The Flatshare is a delight on every single level – possessed of a story that is escapist, fairy floss delightful but also groundedly real and true, it lavishes time and love on its characters, makes them interact in ways that are a joy in and of themselves and not just as narrative momentum fodder, and reminds that life might be difficult and harsh and awful at times but that it is also the repository of escapist beauty like love and we should never assume that the former is so powerful it can’t ever yield to the latter.

Of course, when it does, it is magic, and The Flatshare luxuriates in this certainty, gifting us with a story that elevates the heart in a way that feels both light-as-air diverting and seriously honest, and taking us to some very thoughtfully hard but finally life-affirming places in the process.

Space Hopper by Helen Fisher

Space Hopper is empathetic and insightful in this regard, an off-kilter tale that uses the most audaciously out-there of ideas to go to the very depths of a soul in crisis and ask it to ponder what matters most – the present or the past?

Or could you possibly have them both without losing either? (and might you, in the course of the most extraordinary of journeys change others’ lives for the better even as you mourn the loss of what might have been for yourself?)

That is the billion dollar question really, and the driver of the engagingly affective narrative which always keeps its eye firmly on the humanity at the heart of its storyline and never once forgets that we all long for closure, for that magical moment where we get a second chance to make things right.

Or at the very least find answers to the questions that have long haunted our waking dreams, something Space Hopper offers Faye who finds herself simultaneously joyful and trepidatious as her life takes a most unusual and unexpected turn and she has to ask herself what matters most to her and to which part of her life she owes the great allegiance, time and love.

Last One at the Party by Bethany Clift

At turns funny and self-deprecatory, tearily grief-stricken and self-recriminatory, triumphant and hopelessly lost, Last One at the Party is that apocalyptic novel you have been craving, a story that feels unburdeningly real and uplifting and something with which you can wholly identify.

In fact, you come to love the protagonist warts and all because she isn’t horrible or awful or nasty; she’s just fallibly human, like all of us, and trying her best to navigate what feels, much of the time, to be completely unnavigable.

Last One at the Party is so groundedly emotionally resonant that while you recoil in horror at the idea of being that alone, and wonder how you would cope in the same situation – pray it never comes to pass because 6DM makes COVID-19 look like walk through the park – you are assured that for all your failures and frailties and lack of resources and skills, that you might find a way through the morass of loss, grief and crushing isolation, and might become someone altogether different, a person who would rather be anywhere but marooned at the end of history but manages to find a way, against all odds and expectations, to keep the story going in ways powerful and yet altogether understandably human.

Radio Life by Derek B. Miller

A post-apocalyptic thrilled that really understands how little we might change but how much we need to and can, Radio Life is one of the best novels of its genre to come along in some time because while it is grimly honest about what humanity might do itself, not once but perpetually, even after the end of the world should have sobered us forevermore, it also offers hope that we can pull victory from the jaws of defeat and that there might be a future for us after all.

That’s a bold claim in an age when climate change, war, pandemic and rampant national self interest are all ablaze with no certainty they lead anywhere good, but it is one worth clinging to, if only because if there is one thing we have in our favour, and Radio Life celebrates it with nuanced passion and ardour, it’s that we are innately curious and tenacious people who, time and again, have shown we can stare disaster down and rise triumphantly from the ashes.

Could that happen again in a far or distant future, or even now? Quite possibly, reasons Miller who, though not even remotely glib about our prospects – he is nothing if not honest which adds a necessary substance to this beguilingly inspiring piece of work – seems to think we have it in us to make something of the very worst of things, a message not simply for those of the Commonwealth but for those of us here and now as we stare down a rough and uncertain path ahead.

The Emporium of Imagination by Tabitha Bird

The Emporium of Imagination is that rare and astoundingly wonderful book that balances how grim life can be with how upliftingly alive it can be too.

As Ann and Enoch come to grips with their respective losses, but also come to realise that there may be something to gain too, something beyond their imagination and as impossibly wonderful as the Emporium itself, we are also taken on a journey with Earlatidge who suddenly discovers he is dying and that he will need to face up to his own tragic past if he is to have any peace in the next.

The beauty of this exquisitely well-written book, which is both magically real and light and substantially weighty and affecting too, is that speaks to the idea that another life is possible after the heaviness of grief has fallen on you.

If you have ever struggled to get back up after great loss, as this reviewer has since losing both parents within three years of each other, you will see much of your own journey in these imaginatively wrought but insightfully grounded pages which admit that death often takes a devastatingly big bite out of life such that you wonder if the wound will ever heal, but that with or without the presence of The Emporium of Imagination in your life, you can rise back to a life worth the living, and while it may not look like the one you lost, it might, in its own magically alive way, take you places you thought had long ceased to be within the realm of possibility.

Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro

It is her ability to watch and not simply mimic but live out what love seems to her to be, and truthfully, she gets it right more often than she doesn’t, that fills Klara and the Sun with so much humanity that the protagonist seems on her own to make up for all the deficiencies of her found family and indeed, an entire society which seems to have lost its way.

This is a society that has gadgets and toys, possibilities and technological wonder but which seems to have forgotten what it means to value another person without taking into account their intelligence, productivity or economic value, and simply just loving them for them.

But Klara, despite witnessing this brave new world in action, doesn’t miss that loving someone simply for who they are, the way in which for instance she instinctively and wholly and without condition loves Josie, is what love really is. and she lies it out every single day of her life, wherever she is.

Klara and the Sun is yet another fine and intelligently affecting entry in Ishiguro’s superlative canon, a novel which takes as its emotional beating heart an artificial being who should ,by rights, be the least human of all the characters in a sharply observed, emotionally resonant book, but who becomes the most human of them all and transforms our idea of what it means to love, to truly love, in the process.

The Coward by Stephen Aryan

Much like The Lord of the Rings, which was grand and epic in the scope of its adventure and yet well aware of the weight of the darkness that darks all of us and the world around us, The Coward is a magnificently enthralling tale that regales you with creatures of terrifying ice and mist, heroic battles to stay alive and finish the quest, and the tight bonds that form between people when their backs are well and truly against the sub-zero wall.

A fantasy with considerable heart, a knowing sense of the truth of things, and a willingness to peek behind the myth and legend to the cold, hard reality of what it means to be human (or otherwise) and caught up in the messily contrary and exacting business of being alive, The Coward is a brilliantly good read, a novel that seizes the imagination, hold the heart close and stares hard into the soul, all the while reminding us that we can hold adventure and terror in balance and perhaps this is the very inescapable stuff of being human.

Project Hail Mary by Andy Weir

Weir is one of those rare writers who somehow manages to keep narrative and its building blocks, including scientific exposition and startlingly good characterisation, superlatively good tension, with both present and accounted for but not at the expense of the other.

As a result, while a great deal of scientific explanation fills its pages, its delivered in accessible, story-friendly fashion, helped along by the fact that Ryland is one of the best protagonists to come along in a science fiction novel for quite some time.

Leaving aside just how alone Ryland is – that in itself is an intriguing part of Project Hail Mary that delivers tenfold – He is one of those lead characters who is funny, smart, capable, grounded and delightfully though not fatally fallibly human.

Having him go through this most demanding and harrowing but also hopeful and rewarding of stories is a rare delight, because he is so damn relatable, the perfect person, even if he doesn’t think to possibly save the world.

Project Hail Mary is an astonishingly good, funny and deeply rewarding read, a novel which takes us to the very end of ourselves, and Ryland to the end and new beginning of himself, all while setting off on a journey into the very far reaches of the galaxy from which our salvation, in forms we never see coming, might well manifest and from where we may learn about life and its capacity for breathtakingly surprising survival, than we ever thought possible.

Dreamland by Rosa Rankin-Gee

There is nothing fairytale about this world, which finds itself evoked in writing that is both searingly serious and unexpectedly funny (how else do you deal with day-to-day disappointments without a heady sense of the ridiculous), and Rankin-Gee never once pretends otherwise; however, the weight of so much misery and extremist hellishness does not then preclude any sense of optimism, however tenuous, which finds expression in ways that will surprise and enthrall you.

If Dreamland is the future, and Rankin-Gee does make an alarming case for it being just that if current trends hold true, then many of us are in for a whole world of pain, especially those most at risk on society’s margins, but what’s important to note, and it finds buoyant liveliness in the person of Chance, is that even against something this nightmarish, hope and love might yet persist, testament if nothing else to the tenacity of the human spirit.

Day Zero by C. Robert Cargill

The bond between Pounce and Ezra is formidable and enduring, proof that while angry robots and plasma guns might pack a punch, selfless devotion makes even more of an impact.

After all, it powers Pounce’s desperate mission to save Ezra but it also helps the nanny robot to work out that he is doing what he is doing, in contravention of the majority of his kind, because he alone has chosen that path; he is influenced but not defined by his programming, a powerful nature vs. nurture discussion that percolates all the way through this tense and wondrously good novel.

It is a rare thing to have a narrative so chillingly, excitingly intense and yet so beautifully, authentically emotional but Day Zero delivers on all counts, a rich and true story that cuts right to the heart because it remembers that even at the bloody horror story that is the end of the world that love can endure and while it might not triumph in the way you think it will, it can still powerfully and transformationally affect the course of seemingly preordained events and sustain itself even as the new powers in town call on to abandon all hope.

But love doesn’t work like that, and in Day Zero celebrates it strength and power just as much as he holds aloft what real freedom of choice looks like and that we relinquish it at our personal and collective peril.

Dog Days by Ericka Waller

What makes Dog Days even more of a joy to read and which will have you wishing you could stay in Waller’s evocatively made world for as long as possible – 357 pages is pitch perfect long but still feels not long enough because who wants this sublimely wonderful take to end? – is the way in which Waller weaves together, with exquisite thoughtfulness and care, the dark and the light of life.

In many stories, these two elements feel discordantly at odds, as if only one can occupy the space of a person’s life at one person, but in Dog Days, it feels entirely natural, because it is, that happiness and sadness, hope and despair, can co-exist in the same agonisingly imperfect time and place. (This truthfulness also comes with a warning that you should not judge others because you often only see one of these strands or a small snippet of their life and cannot possibly know or understand the full scope and state of their life.)

Dog Days, for all its whimsical hopefulness and cheery optimism, is darkly grounded too, a salient and reassuring reminder that being in a place of brokenness, while entirely human place to be, is not the end of things but that where is takes you can surprise you and that there is a richness and a life-changing value in simply opening yourself to where the broken places might take you.

The House in the Cerulean Sea by TJ Klune

The House in the Cerulean Sea is a vivacious joy because it not only celebrates how glorious it is to be different but also makes it reassuringly clear how often even in that difference there is a commonality of human experience that the small-minded and the bigoted miss on their cursory assessments of those who don’t fit their idea of normal.

In its own quirkily upbeat and happily determined and tender way, The House in the Cerulean Sea gloriously celebrates how good it feels to find your special place in this world, one which can diabolically cruel and nasty but can also offer the type of unconditional love and acceptance that so many people of all shapes, sizes and types crave and deserve.

That Linus finds this is a beautiful, heartstoppingly wondrous thing but that we are taken on this life reshaping journey with him is a real treat and privilege, something that anyone who has ever felt outcast will love, adore and cling to, proof that we are never alone once we find our family with the book also a reminder that once we find them, we must hold tight to them, fight for them and treasure them for the rest of our natural, or unnatural, life, whatever the case may be.

Swashbucklers by Dan Hanks

It’s that sense of yearning for your childhood while being unable, and often unwilling to forego the responsibilities of parenting – Cisco may not be the world’s best dad but he does love George and that really what counts in the end – that really gives Swashbucklers that extra special dash of something serious and ruminative in what is a thrilling full speed ahead, cracking good race to stop evil from destroying the world, and many others besides, against a ticking clock.

And all at Christmas too when thoughts should really be turning to peace and goodwill, eggnog and street markets, and not, thank you very much, evil creatures from the most frightening corners of our imagination who, it turns out, are a whole lot more real than you, or Doc, Michelle and Jake might think (Cisco, of course, does know which is a great part of the burden he carries and the existential angst which is a near constant presence for him.)

Thankfully for Cisco and his band of exhausted fighters of darkness they have the help of a magical talking fox, a man made of boulders, and a host of other beings from sprites to gnomes from which they will definitely need help as a romp through an enchanted forest, accompanied for Cisco at least by the whispered cries of a long-lost friend, becomes altogether more serious.

Swashbucklers is all your fondest ’80s adventure fantasies sprung gloriously and soul-stirringly to life, writ large against a massive battle to save the soul and physicality of all worlds, but it is also richly so much more, offering up ruminations on the chasm-like gap between childhood and adulthood and how we never really leave who we were as kids behind even as we struggle to live as fully-functioning adults.

The 24-Hour Cafe by Libby Page

When it comes to Hannah and Mona, The 24-Hour Café is a glowing testimonial to the power of friendship to survive pretty much everything you throw at it, though not without some hurtful collateral damage from time to time, taking the time to let us get to know how they became friends, stayed friends and weathered the tumult of life can test even the resolve of best friends to stay there for each other.

There is so much about this wonderful book that rings true, from its encouragement to see those around you not as strangers but unknown people with whom you are connected simply by being alive and in the one crowded, amazing place, to its touching exploration of the minutiae of people’s lives which are rich in truth and emotional resonance, through to the beauty of real, deep and lasting friendship without which we are the poorer.

Stella’s may be a whimsically quirky place that becomes its own memorable character in The 24-Hour Café but ultimately it is the setting for stories big and small, a reminder that whenever we feel we are alone and disconnected from everyone around us, that connection is just a step or a burger order away, and that by taking a chance, we might find life can surprise and delight after all, especially when we are at our lowest point.

Still Life by Sarah Winman (#1 for 2021)

This title is my #1 pick for the year, and rather happily also of my favourite bookstore in the world, Dymocks, in Sydney City, which gave it the award for 2021 Book of the Year, which the author, Sarah Winman, responded to in a rather delightful video ...

Writing with wit, wisdom, insight and an affecting understanding of the human condition in all its boundless difference and mainstream nonconformity, Still Life is one of those rare novels that knows the world is unremittingly difficult and harsh but which counters that love, real muscular, warts-and-all love, is more than up to the job of dealing with it.

More than simply dealing with it, love is able to stare life in the eye, daring it to challenge what it has created and demanding that it yield to the close bonds of family and belonging, selfless love and care and a boundless generosity of spirit that than can handle pretty much anything.

There is so much rich loveliness and human beauty in Still Life, a delightfully enriching story that is told with luxuriously good language, cleverly, humourously and affectingly used, a deep appreciation for the majesty of well-wrought characterisation, and a real sense of how bad life can be and how broken people are, and yet how much love can counter that in ways that are far from lightweight and fleeting but which can change and influence people over decades, all of them the better for having given themselves over to its unconditional and all-encompassing power and life-altering influence.

Winter’s Orbit by Everina Maxwell

Space opera in and of itself often rise and fall on the basis of extravagant worldbuilding, big stakes and ceaseless narrative momentum but the good ones, the really good ones, also deliver up characters so well-formed and memorable than they make the story come even more fully alive.

Winter’s Orbit is very much in the “really good ones” camp, a tale that is as big as a galaxy but as intimate as a quiet moment between feverishly invested lovers, and which consumes you in the very best ways as you wonder if the Empire will survive, but just as importantly if true love can bloom and be sustained in circumstances that seem all but inimical to it.

The Sweetness of Water by Nathan Harris

Selected as one of Oprah’s Book Club entries for 2021, this is a novel that will change your heart, mind and soul, an achievement made all the more impressive because it does not rely on big noisy plot twists, though some are in evidence and are used well, but rather the nuanced expression of people who refuse to let go of hope but are all too aware that a great many things, and people, stand between them and the realisation of hope’s potential.

And certainly there are a great many times when each character, all of whom are close to each other and yet not, could reasonably assume that the obstacles are too great and the promise too far off to be of any real good.

Alive with as much artistry as profoundly touching humanity, The Sweetness of Water is a brilliantly immersive book, one that subsumes you in a world that feels eerily relevant to the divisions that blight American society today and yet which also echoes the sort of hope that impels people today to stand up to tyranny and bigotry, even at great personal loss.

Certainly the Walkers, who are viewed with simmering suspicion by the people of Old Ox because they dare to employ Black freedmen in the same way as a white person, face the real loss of everything they hold dear, and the enveloping, resonant brilliance of The Sweetness of Water is how it makes those threats real and palpable, driving a narrative full of as much danger as sustenance, while also reminding us of the power of hope to drive people to take great risks, stand up for what is right and to go far beyond where they have ever gone before, geographically and existentially, in the pursuit of a life far better than the one they currently know.

Hush by Sara Foster

You care deeply about these three people, all of whom in their own way are fighting back against the idea that you should be complicit in nascent tyranny, that the only way to cope with looming dictatorship is to keep your head down and hope no one notices you.

These three brave women, each in their own way, come to appreciate that they must take a stand, that they must do something, and that it’s simply not enough to sit by and watch the world go destructively south because while you may not be in the firing line now, there’s a very good chance you will be later and you can’t wait for that to happen.

It does happen, of course, we wouldn’t have a thrilling read if it hadn’t, and it’s reading about how ordinary people like Lainey and Emma in particular find a bravery and resourcefulness to fight for their own lives, for the rights and freedoms of friends and family, and for society as a whole, that makes The Hush such a powerfully engaging novel.

While you may initially think the ending comes far too suddenly, upon reflection it ends precisely when it should, both in terms of job done and emotional connection restored, a final high note in a novel full of them.

The Hush is one of those rare precious books that barely puts a foot wrong and which captures both the grinding sense that something is very wrong with the world, but thankfully also that hope is not futile and that you may be able to make real change happen even in the face of insurmountable odds.

Happy Hour by Jacquie Byron

Happy Hour is content at every stage to simply let life follow its own inevitably wonderful but flawed and broken at times path.

And we are all the richer for it as we witness Frances slowly but far from easily begin to slowly make her way out of her three-year long shutting out of the world and the Salernos, in need of a fair amount of healing themselves, draw her into their world which is much in need of someone like Frances, even if she doesn’t realise it yet.

In a year where Australia’s two largest states by population and its capital territory have been locked more often than not in lockdown, causing all kinds of relationship ruptures, Happy Hour is like a balm for the sad and lonely soul, a timely reminder of the immense power and value of connectedness.

But it also sagely knows that while being connected with others is indisputably good, that sometimes we are so lost in the dark times of life that we fail to see this, the forest out of sight because of the grief-laden trees.

Byron gets both the barrenness and necessity of grief but also the joy of having people love and support you unconditionally, and how the two might feel diametrically opposed but in the end, fit together beautifully in ways that Frances, who is absolutely someone you will wish again and again was your next door neighbour, comes to appreciate in a novel that will steal your heart, speak to your mind and enrich your tired and weary, and perhaps even sad soul, in ways you didn’t even know you needed.

Light Chaser by Peter F Hamilton and Gareth L. Powell

The novella is one of the best sci-fi stories this reviewer has read all year, not only because it tells a compelling tale but because it does so with an economy of delivery paired a breathlessly expansive imaginative scope that shines a chilling light on what happens to people when they discover that what they thought to be true is anything but.

It can either crush you to the ground in an effective pulp or embolden you, and once Amahle begins to realise that the threat is real, the person articulating it even more so, and that she will likely need to sacrifice everything to set it right, she is emboldened in a way that sets your skin on fire and wakes you up in ways that makes you feel the most alive you’ve felt in ages.

While Amahle’s life is changed beyond all recognition, it’s what might happen to humanity to a whole that really enthralls you, and how she might be the only one capable of fixing some grievous wrongs that have been done.

Light Chaser is a superlative piece of writing, a thrilling piece of sci-fi that elevates character, premise, worldbuilding and mystery to an overwhelmingly exciting degree while keeping its feet very much grounded in the humanity of one person facing up to the once-unknowable and mow unmissable, a realisation which will shake her reality to the core, but which in doing so, could prove liberating to others in ways to audaciously powerful to fully comprehend, the effects of which will reverberate long after Amahle has shuffled off her too-long-occupied mortal coil.

Trashlands by Alison Stine

What makes reading Trashlands such a pleasurable thing is that while it is brutally honest about the horrific mess we have made of the world and how it could potentially affect future generations, and the medieval darkness of capitalism and greed left to run unfettered, it is also firmly in its belief that there remain things worth fighting for.

It’s not glib or casual about it by any means, with people like Foxglove and Summer forced into virtual slavery to survive (though even they have found sweet moments of connection and love that sustain them) and Trillium, who scavenges ink to do tattoos on strip club visitors and Coral barely scraping by, and it knows any hope is hard won, but nevertheless, it maintains it is not an antiquated idea and worth pursuing, if only because the human spirit is ridiculously tenacious and won’t let go off it even when everything says it should.

A celebration of love, family and belonging where the sheer race to survive should by rights have spun everyone into their own bubble of murderous survivability, Trashlands is a sage warning about present inaction leading to future hellishness, a sobering exploration of a world given over to survival without living, and how despite all this, humanity not only survives but miraculously thrives, and while lessened, is over and done with just yet.

Harlem Shuffle by Colson Whitehead

Using language that is both beautiful, vividly descriptive and emotionally intimate, all of it a feast for anyone who loves words which not only sound good but say something thoughtfully meaningful too, Whitehead bring alive Harlem in the 1960s which will delight and envelop in some impressively evocative worldbuilding, social commentary and examination of family dynamics.

Harlem Shuffle is a perfect blend of a great many things being both incisively observant and empathetically grounded, alive with possibility and weighed down by limits, and understanding of the fact that try as we might to forge our own path through life that our pasts have a way of coming back to pull us back to places we may not really want to go.

The brilliance of Harlem Shuffle is the way it immerses us in the society of the time, and in Ray’s life within it, a love letter to a place and a time that moves you with exquisitely well-wrought language, characters who are as live as the period from which they hail and insights on society, life and humanity which find their affecting distillation in the person of Ray Carney, a man who wants a great deal from life if only it will let him have it on his terms.

How to Survive Family Holidays by Jack Whitehall (with Hilary and Michael Whitehall)

With sage holiday tips, wry observations and rueful understanding that what could go wrong can go wrong, Whitehall takes us through perilous Christmases, chaotic plane boardings with unreserved seating and toilet misunderstandings in Spanish restaurants – that passage, ahem, alone will have you on the floor in a guffawing mess (and yes, I read it on a train and had to fight hard not make a complete spectacle of myself; not sure I succeeded) – in a book that somehow manages to make holidaying with your family not seem like the worst thing you can do.

How to Survive Family Holidays is, for all its hilarious anecdotes and familial honesty, an affirmation of the fact that while they might drive us mad and question our good holidaying judgement, that families are wonderful things and that while we might gripe and moan in the interim, we will miss it when they are gone.

For now, we have a very funny book to read, a tome full of such blinding honesty and rueful comedic perfection that you might be compelled to go on a break with your family just to see where it all may lead … or perhaps maybe just read How to Survive Family Holidays and ponder what might have been?

Stringers by Chris Panatier

If you have ever wondered whether there is any real off-the-charts original imaginative storytelling left in novels, and frankly where you have been since there is plainly lots (we are in a golden period of authors breaking all the genre rules and more power to them), then Stringers reassuringly and without apologies shouts “YES!” from the top of an immense spire in a city the size of a moon (again, this will make much more sense later).

Throughout Stringers, with its wacky, brilliantly wonderful, healthy dose of imaginatively ladled-out bug facts, Panatier adds real heart and soul, an offbeat way of looking at life that you will heartily embrace, and then some, and a story so breathtakingly different and unique that you will wonder if you are fit for any subsequent stories set in space.

Of course, the answer will be yes, but in the meantime, wallow and glory in the vividly unusual and expansively rich and funny delights of Stringers, a novel which takes an inspired premise, runs with it, very humorously we should add, and offers up a story that is so out of this world and yet so groundedly human that you will need a jar of pickles, backward text and hilariously informative footnotes just to deal with it, and deal with you shall in ways that will make you wonder how you ever lived without this gem of a novel.