Every single film you watch, for better or worse, should be able to take wholly and completely into the world it creates.

Sometimes that is not a good thing but in the case of films as luminously moving and meditatively complex as C’mon, C’mon, written and directed by Mike Mills (20th Century Women), it is a very good thing indeed with narrative, lyrical and visual flourishes giving birth to a world that feel instantly familiar and yet far enough apart that it feels like you are somewhere utterly removed.

Shot in black-and-white, which in this case is not an artistic affectation of any kind but a masterstroke move that lends the film a unique sense of time and place, allowing the audience to lose themselves in the dialogue and character interplay which is so essential to the story.

It’s hard to say precisely why black and white filming works so brilliantly well generally, but specifically in the case of this ruminatively immersive film.

Perhaps it could simply be the novelty of seeing an entire film in monochrome in an age of dazzling digital colour, or maybe it’s the subtlety of contrasts that creep into each scene that you may not otherwise notice if the film was in the usual colourful hues; whatever it is, there is a real beauty to C’mon, C’mon which is given even more visual heft by the inspired cinematography of Robbie Ryan.

Some scenes are viewed from afar, as if we’re a neighbour watching the world move around us from a distance, and at no time, despite the lack of closeness, do we feel as if we are removed from whatever’s going on; in fact, the use of far-off shots helps the film to feel like an intimate real life experience where we are coming and going into the lives of the various characters whose lives are, initially at least, not in the very best of places.

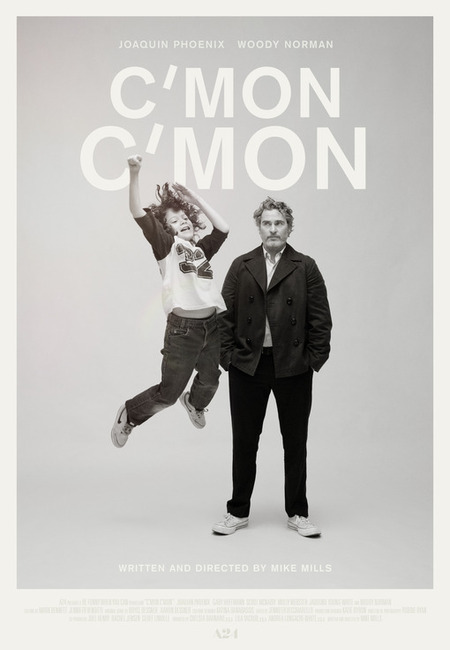

Interspersed with interview of American kids and teenagers talking about everything from their hopes for the future to the yawning gap between adults and children, C’mon, C’mon introduces us initially to radio journalist Johnny (Joaquin Phoenix), whose work is featured topping, tailing and adding extra existential weight to a film already welcomingly and lightly heavy with it, and who spends his time criss-crossing the country with is production partners.

At one stop in Detroit, he is alone in his hotel room and on a whim, calls his sister Viv (Gaby Hoffman) with whom he hasn’t been in contact for a year following the inevitable trauma that follows from a parent’s death, in this case his mother who we see, in sparse flashbacks (which never slow down the narrative but always feel organically a part of it), he and Viv nurse through the harrowingly painful end stages of dementia.

Not an estrangement as such and more a familial catching of collective breath, the two are soon talking again and towards the end of the conversation, Viv asks whether Johnny would be willing to come and look after his delightfully idiosyncratic nine-year-old nephew Jesse (Woody Norman), while she navigates her estranged husband Paul’s (Scoot McNairy) latest out of control bipolar episode.

While this coming together of long-separated uncle and nephew at first proves to be a handful, it becomes a game changer for Johnny – and Jesse too, who isn’t handling his father’s absence and mental health issues as well as he makes out – who as well as trying to handle parental bereavement is stuck in the messy aftermath of a romantic break-up.

While it’s awkward at first, and there are moments where Jesse, who has to accompany Johnny to New York (where he lives) and New Orleans, and Johnny clash, there is for the most par a slow-moving but enriching meeting of hearts and minds that lends the film the reassuring sense of a family belatedly but profoundly knitting itself back together.

At no pint does C’mon, C’mon pretend this is easy or straightforward but then nor does it throw unnecessary trauma and obstacles in the way of the characters either; at every narrative twist and turn, which are gentle though emotionally powerful rather than wrenching for the sake of it, it all feels natural and organics with the back-and-forth, ups-and-downs of Johnny and Jesse’s relationship feeling the accessible stuff of normal life.

While it has the air of a meditative rumination on everything from love, marriage and commitment to parenthood, and the great parent/child divide, C’mon, C’mon packs quite the emotional punch.

It’s clear that in variously different ways that Johnny, Jesse and Viv need to come to terms with their lives as they are, post-mother’s death and in the midst of Paul’s illness – in the complicated history of Johnny and Viv, there’s some residual rancour that Johnny’s advice was for Viv to leave Paul, something Viv simply couldn’t do at the time, and still can’t – and that they haven’t done that successfully to date.

This is clearly an issue for Jesse who lives in his own sweety eccentric world where he often pretends he’s an orphan – a telling indication the estranged nature of his emotional state if ever there as one – forcing Viv and Johnny to answer questions about what his family was like and he misses them.

While Johnny initially rejects Jesse’s decidedly odd way of dealing with the trauma of his broken, though loving family, he soon realises this is his nephew’s way of dealing with it, and without any clear plan of what to do (he relies, on Viv’s advice on parenting prompts via Google, which leads to one gorgeously meaningful scene with a clearly amused Jesse), he slowly builds a relationship with his nephew that leads, in some, tense, funny and realistically touching ways, to them both finding some accommodation with a seriously f**ked up present.

Every step of its narratively and visually, character-rich way, C’mon, C’mon is a quietly immersive joy, a film which might look wholly separate from the cinematic pack but which feels warm, alive and quietly in touch with what it means to be human, all too aware that for all the good things life can offer like family and belonging, there’s a host of dark and terrible things too, none of which it groundedly maintains should be fatal if you’re open to be real, honest and importantly, willing to put in the time to see where, together with those you love, life may take you.