The universal question that On the Road poses almost from the first frame is this – at what point does a damaged person’s need for self preservation become a narcissism so malignant it becomes poisonous to everyone around them?

It is a question worth asking especially in a world where more people are broken than they are whole, and are searching for anything that will ease the pain.

Unfortunately for On the Road, which is as uneven as it is fascinating, it is a question it often forgets to answer until almost the dying moment of the movie, and then only halfheartedly and with an almost cursory ticking of the box.

To be fair that’s partly because the movie is ostensibly the story of Sal Paradise (Sam Riley), the son of Quebecois who emigrated to the USA, specifically New York City in search of a better life, and who yearns to be a writer, surrounding himself with pretentious but well earning, earnest friends who debate the meaning of life at every available opportunity, and who spends many hours staring fruitlessly at the blinding white blank pages in his beloved typewriter.

Sal, who is essentially Jack Kerouac, a renowned figure of the Beat Generation, in fictional form, yearns to be something, anything and when he is introduced to Dean Moriarty (Garrett Hedlund) an ex-con from Denver with a flair for “living” and a remorseless appetite for adventure and self-indulgence, one night shortly after his father’s death, he thinks he has found what he is looking for.

And for a while he does. With his wagon hitched to the ceaseless headlong rush to nowhere in particular of Jack Moriarty, Sal is introduced to a life on the road that is equal parts unbridled hedonism, wanton disregard for the social niceties of life, and a corrosive eroding of many of the moral underpinnings that govern normal every day interactions, with a small dose of freedom thrown in.

But as Sal eventually discovers one night in Mexico, which he is lying desperately ill in a sweat-soaked hotel room in Mexico, a victim of a particularly nasty batch of peyote, that freedom, such as it is, is fleeting at best, and only exists at the whim of Dean who leaves him alone, off on another adventure to god knows where, life with Jack comes with a price.

It takes Sal a lot longer than most other people who fall into Jack’s orbit to discover that his best friend, whose name I suspect is no accident and a deliberate reference by Kerouac to the preening narcissism of Sherlock Holmes’ arch nemesis, is a man who is all direction and no destination, and who, in the words of one of the people damaged by Jack’s careless careening through life observes (and I paraphrase here) doesn’t feel he owes anyone anything but feels that everyone owes him everything.

Sal fails to see time and again that Jack is a restless spirit who, disturbed early on in life by a broken family, and the haunting absence of his father who may or may not be a bum on the streets of Denver, who is unable to ever truly settle down.

Oh he tries again and again – with the bright and shining hope of Camille (Kirsten Dunst), whom he meets when she is an eager student studying set design and who fatefully becomes his second wife giving up all her dreams in the process (and gives him two children he adores), and with Mary Lou (Kristen Stewart), his first wife who he marries when he is 16 and with whom he comes the closest to some facsimile of real love.

And even with Carlo Marx (Tom Sturridge), one of Sal’s troop of questioning intellectuals and a gay poet who foolishly falls in love with Jack, only to find his wish “to be held” spurned, which stirs up his always present suicidal urges.

But it is Sal, dear faithful Sal, a man in search of the great novel he knows lurks deep inside of him if only he can unleash it, and the cause of his own inherent restlessness (which is nowhere near as insatiable as Dean’s variant) who fails to see the truth about his reckless friend, almost until it is too late.

It takes a lot of sex-drenched, drug-fuelled trips back and forth the USA – usually between the three cities of New York, Denver and San Francisco that are the geographic touch points for the cross country shenanigans – at high speed (speeding tickets are a recurring motif for the motley crew) for the penny to drop.

And that’s after he is witness time and again to Dean’s destructive effect on so many friends, and even strangers (including his own mother who endures a hair-raising trip home one Christmas), and a particularly frank discussion with eccentric writer Old Bull Lee (Viggo Mortensen) where he point blank tells Sal he is friends with a man who is “psychotic” and “pathological”.

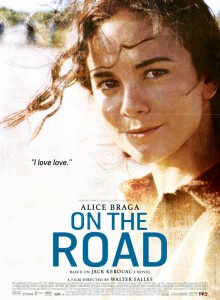

Yes, all these messy life experiences are enthusiastically embraced by Sal, who we also see in quieter moments on the road working on the railroad and picking fruit with his lover Terry (Alice Braga) and writing, always writing till half his luggage is hastily scribbled notebooks and scraps of paper, and they do eventually fuel a writing frenzy that results in the book that documents his travels with Dean, but it all comes at a great cost.

And it’s not just Sal that suffers, though he refused to see that Dean is costing him anything.

It is the audience too as the movie, which in the first two thirds or so is all sharply observed vignettes, and finely nuanced character interaction, descends into a shambolic series of loosely cobbled together moments, and one road trip too many.

Frankly by the end of it, and it’s the scenes in Mexico and a pivotal scene in New York City right at the end that rescue a weak and tiring final third of the film, I was dreading Jack and Sal deciding to go on another trip anywhere. I was hoping that Sal would simply stay at home and knit and drink cocoa, and spare us all another repetitive (and by this stage the shock value of the movie had dimmed significantly and the road trip schtick was set on endless repeat) ride into the vast blue yonder and simply start writing.

Some of the characters too are not as finely etched as they could be. True, many of them such as Steve Buscemi’s closeted cross country driving companion – whose sexual congress with Dean for much needed money triggers a relatively minor schism between Dean and Sal – and Terry are barely in the movie long enough to really make an impact but there is a sense that too much was shoved into the movie in a desire to be faithful to the book and this cost some characters a fully-rounded persona.

All that aside, however, it is a brave and unflinching look at many of the people, in see- through fictional guises, who gave birth to the Beat Generation, a wildly exuberant period in the 1950s when a group of writers inspired a hedonistic period of drug-taking, sexual experimentation and the open and passionate discussion of ideas.

And while it does tend to overstay its welcome a little, before finishing with a poignancy that is far more touching than anything that has gone before it, it is nevertheless, beautifully rendered, well acted and a no-holds-barred glimpse into a world that flickered, grew to full flame and then died almost as quickly as Jack Kerouac brief but brilliantly realised life.